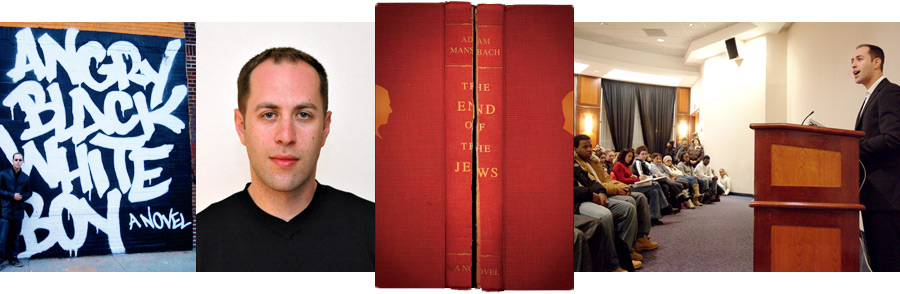

Adam Mansbach books events bio music interviews other writing

| You

and Macon Detornay, the protagonist of Angry Black White Boy,

both grew up in the suburbs of Boston, attended Columbia University, and

immersed yourselves in black politics, music, and culture at an early

age. Where do the similarities between Adam Mansbach and Macon Detornay

end?

Definitely sometime before the moment Macon decides to start pulling guns on people just because they’re white. At least five minutes before. Angry Black White Boy is a satire, so a lot of things are amplified, tweaked, taken to extremes. But certainly, Macon and I share a geographic and cultural background. We both grew up trying to reconcile Boston’s insistence that it’s a really liberal city with all the evidence to the contrary, from the vicious bussing battles of the seventies to the staggering segregation of the city’s neighborhoods to the fact that the Red Sox were the last team in the majors to field a black ballplayer. We’re both products of a mostly-white school system integrated by a program that brought inner-city black kids out to the white ‘burbs –- a unidirectional form of integration, you might say. And we both discovered hip hop and politics at a young age. Back in 1988, when I was twelve, hip hop was a gripping site of critique – the first place I found real validation for my suspicion that that there was another world out there, only a few miles from my house, in which crime and poverty and bad schools and a thousand other symptoms of racism and neglect were savaging the prospects of yet another generation. Macon and I both looked at hip hop and said “why get down with the dominant culture when I can get down with what is taking it to task in a vibrant, brilliantly poetic way?” At that time, there weren’t many white kids on the scene. You had to seek hip hop out where it existed, which meant venturing into other neighborhoods, insinuating yourself into other communities. Being in the minority yourself, for a few hours. Whiteness automatically put you on the defensive, and Macon and I both felt that was appropriate – for reasons that had to do both with understanding the history of white exploitation of black culture, and with self-gratification. There was a duality iof being vigilantly aware of your own whiteness, and simultaneously trying to escape it. The experience of being a token whiteboy was one of being identified, tested, and ultimately accepted, and thus feeling special. It is impossible to overstate the importance of that feeling – for me, the acceptance came from the fact the I could rhyme; that was an immediate way to prove myself. Behind it, for Macon, and for me, and for any white kid drawn to hip hop, lurks an entire pathology about blackness and black people. Easier than destroying that pathology is believing yourself to be an exception to the rule. In a lot of ways, however, despite all these similarities, Macon is an anti-autobiographical figure. He’s the zealot I might have been, but didn’t want to be, or lack the courage to be, or am too old now to be, or see too much grey to be, or, or something. I found other music, I went on the road with Elvin Jones and started dealing with jazz. Macon just has hip hop. It’s the only time signature he knows how to play in. Angry Black White Boy examines the murky racial waters where whiteness and blackness meet in America today, and to what degree whites can participate in hip hop culture. How much further do whites have to go in order to be accepted as equals in hip hop? Part of me likes that question, because it puts the onus on white people, and part of me feels like it’s kind of silly to discuss how whites can be accepted in as equals in hip hop when we could be discussing how blacks can be accepted as equals in American society. Not that the two aren’t linked, because the white desire to be accepted in hip hop is largely a desire for absolution, a desire to shed our institutional and economic privilege symbolically. Not to abandon it, mind you -- just to no longer be held accountable for it. To trade action for identification –- like, if I really feel what 50 Cent is saying, if I really relate to his situation deeply enough, then I’m freed from any responsibility for the conditions that made his mom have to sell crack. I’m his homey now, instead. I’ve jumped the fence, and I’m down. Macon’s character is a vehicle to explore the limits of white people’s ability to be “down.” Can a kid like Macon,, who grew up entranced by black culture and who socialized with actual black people, who is disgusted and outraged by the hypocrisy and detachment of other whites, make a difference? When the crucial hour arrives, and the committment to black culture no longer means getting to feel cool, no longer means having your anger and your identity validated, but actually sacrificing something, what happens? Is there any way to lock white people in, or is any committment they make always going to be instantly reversible? The first thing we have to address – and what Macon takes on, in his own crazed way -- is how to make whiteness visible. As an identity, a shared set of assumptions, a state of economic and institutional empowerment, whiteness is damn near invisible. Like an object thrown into the water, we measure its weight by what it displaces. We speak of ‘minorities,’ but no American has ever checked a box labeled ‘majority.’ If you ask a white person to describe somebody of another race. I’ll bet you skin color or ethnicity will be the first thing they mention. “Jimmy? Oh, he’s a black guy, about three feet tall, with vestigial wings and a big prehensile tail.” Then get them to describe a white guy. They’ll be like “Rick? Oh, about six feet tall, brown eyes, brown hair.” Very seldom will a white person describe someone as white, because “white” doesn’t register -- it doesn’t read as an identity. I give Eminem credit for elevating the discussion about whiteness simply by being a dope MC. That allowed everybody to stop talking about whether a white kid could compete lyrically, and move on to talking about what a dope white MC meant, which is a lot more interesting. And I give Em credit for bringing a narrative into hip hop about what it looks like to be poor, white and urban in America. It’s often self-serving, because his legitimacy hinges on class trumping race – like at the end of 8 Mile when he wins the battle by unmasking his competitor as middle-class, and thus less real than Em because even though he’s white, Em’s from the streets. That’s problematic, because class is mutable and race is not – Em can make money and transcend his class position, but the black kid he battles will always be black. Mostly, though, Em is careful; he will never, ever play the race card, because he understands that he’s in another cultural space, and he respects the fact that he’s a guest in that space. You might hear every other offensive word from him, but never the N-word. For a book that portrays a present-day white man trying to be accepted into the living rooms of America’s African-American community, there isn’t any reference to Eminem. Was this by design? It’s funny, I just got a call from Adam Bhala Lough, who’s directing the film version of Angry Black White Boy. He said, “Dude, have you heard Em’s Macon Detornay song?” It turns out that on his new album, Em talks about X-Clan, and the Afrocentric fashion trend they started, and how alienated he felt from it. Macon reminicses about just that, early in the book. It’s a very specific kind of memeory – you’d have to be white hip hopper who was not only around in 1990, but also embedded in the kind of black communities where X-Clan was important. My book is set in 1998, when Em was just emerging, which provides a nice excuse for not having to muddy the story by having to make the comparison. But in a sense, both Eminem and Macon take up a position historically reserved for a certain kind of media-savvy black figure. The job description is basically to be vocal, visible, articulate and uncompromising, to inspire a certain kind of very productive fear in white people -- a fear that you speak for all black people, and that if something doesn’t change one way, it’s gonna change another way. In other words, if you don’t get down with King Jr’s program and give him what he wants, then you’re going to have to deal with Malcolm X, and you’re really not gonna like his way. The balance of fear is very important to progress in the country, unfortunately, and the Black Media Radical – Malcolm, Eldridge Cleaver, Minister Farrakan, Khallid Muhammad -- is an important figure in maintaining that balance, in forcing white people to pay attention. In the early nineties, a vacancy opened up, and into the void stepped rappers, whose take on the Black Media Radical position was a little short on political sophistication, but very long on straight-up menace. The job became Angriest Black Man in America, and Ice Cube took it over. When the LA Riots happened in ‘92, he was the one they interviewed on Nightline -- and remember, this was in an era when rappers were not visible on TV at all, except on Arsenio Hall, or maybe MC Hammer dancing in Kentucky Fried Chicken ads Tupac took the position over it, and remade it in an embattled-artist mode -- let you see the internal struggle of the revolutionary versus the thug. DMX grabbed it for a minute, didn’t really know what to do with it. Bill Clinton pretended that Sister Souljah held it in 1992, and attacked her to prove to moderate voters that although he might play the sax on Arsenio, he was still willing to put black people, and hip hoppers, in their place. And then, in the late-nineties, the acculturation of hip hop advanced to the point where, while they might not like it, or understand it, white people gradually stopped fearing rappers -- not necessarily hip hop, or the concept of blackness that hip hop put forth, but the visible spokespeople of that culture. So we’ve gotten to the point where the title of Scariest Black Man may well be held, in a sense, by a white boy. A Macon Detornay or an Eminem. These are figures who represent a symbolic point of no return -- a moment when cultural crossover from the center of privilege toward the margins, becomes irreversible. The fear is not of Ice Cube, or Malcolm X, coming to your house to demand payback -- it’s of your son turning into Eminem, and calling you out, forcing you to confront your own assumptions. And that’s a very different kind of fear. And Macon does not have kind words for another seminal white rap group--the Beastie Boys. Naw, man. You gotta remember, when they first came out it was not all about Tibetan Freedom Concerts. They were some abrasive, non-lyrical frat-boy jackasses, spraying beer at people, and suddenly that was the expectation of white rappers. They kind of clowned the culture by clowning themselves. Macon had to take pains to distance himself from them – and they were the only white rappers with visibilty, so that wasn’t so easy to do. In Angry Black White Boy, you also interweave a poignant story about major league baseball’s first African-American player, Moses “Fleet” Walker. Why did you choose Walker and what was the purpose of telling his story in the book? I included the Cap Anson/Fleet Walker story for several reasons. First of all, I wanted the novel to have a historical dimension, because it’s important to realize that when we grapple with race today, we’re also grappling with history. Our ancestors, and the crimes committed by and against them, are the iceberg; we’re just standing on the visible tip. The theme of overcoming or succumbing to family history, of making amends, the whole ‘sins of the father’ notion, is important to Angry Black White Boy – I mean, one of the first things we learn about Macon is that he has chosen to live with the great-grandson of a man almosty lynched by his great-grandfather. He and Andre are the inheritors of a specific legacy of violence, as well as a broader American one, so there’s kind of an added weight and subtext to their relationship. It was also important to me to counterbalance Macon’s voice and the book’s narrative voice with another, something that spoke from a different time, with a different rhythm and sensibility and wisdom. Sports, and baseball in particular, have been the site of so much crucial social history, and Fleet Walker is from a chapter of that history that very few people know about. Fleet was a fascinating man, and all the facts of his life as presented in the book are more or less true – he did pull a pistol on a heckler, he did write a back-to-Africa tract, he did go to Oberlin College and kill a white man and plead self-defense and get acquitted. Although the game itself is all made up. In the book, Macon commands the attention of the country to honor a “National Day of Apology,” a day when whites should apologize to blacks for past racial transgressions. Do you think America should hold such a day? Well, I think there’s a fine line between calling for honesty and empowering people to act even worse than they already do. In the book, the Day of Apology gets people to approach race, but it’s a cult of personality, and it’s insincere and self-gratifying and confused, and Macon knows it, but it’s still exciting because it’s something. And of course, the Day of Apology is a disaster, and leads to a huge riot. We do need something along the lines of an apology, a day of atonement. I don’t necessarily think it should take the form of people approaching each other randomly on the street. But there needs to be a huge push toward dialogue, and I’m down for whatever will bring people to the table. Fear, free television sets, whatever. I’m down for pressuring the government -- or anybody else, for that matter, from Goerge Soros to George Clooney, Dr. Huxtable to Dr. Dre -- to put enormous amounts of money into encouraging people to get together on a local level, in the freakin’ high school gym if necessary, and trying to be honest with each other. Everybody gets a month of free cable, or a two hundred dollar parking ticket exemption, if they show up, and stay -- but they gotta say something. Tonight’s topic: hip hop. Affirmative action. Primary school education. Whatever. It doesn’t even have to be about race -- it could be something of universal concern that intersects with race. Like law enforcement. Take the police as a topic, and have everybody discuss their perceptions -- play that old Richard Pryor routine about how whites and blacks feel differently about cops, get everybody to share a laugh, then open the floor. Have a goal, however modest: we want to write a letter to the police department, evalauting them, and we want everybody here to agree to the point where they’ll sign it. Get on some WPA shit -- put Cornel West and Mike Dyson and Tricia Rose and Chuck D and Jeff Chang and Robin Kelley and Ras Baraka and Tim Wise and Robert Jensen and Tavis Smiley and nine hundred other committed, capable people on salary to moderate, and assign seating so you don’t have white and black and Asian blocks and Latino, and gradually try to draw people out, find a language that works. Devote a whole night to a succession of young black men testifying as to how difficult it is professionally to overcome the pereception that they’re thugs. Let some white soccer mom raise her hand and say “well then, why do you dress like that, with your pants so low and your T-shirt so big?” Let the dude answer. Draw out whatever goodwill there is -- and it does exist, it just has to be accessed. I think the first few steps will actually be the easiest, because we’re so separate and so mysterious to each other that it will take a little while before anybody hits a major vein, and maybe by the time it happens a slight sense of community will have crept into the proceedings. It all sounds absolutely batshit ridiculous, I know. But this is America. We perfected ridiculous. |

Adam Mansbach books events bio music interviews other writing